Practicing Diagramming Functions#

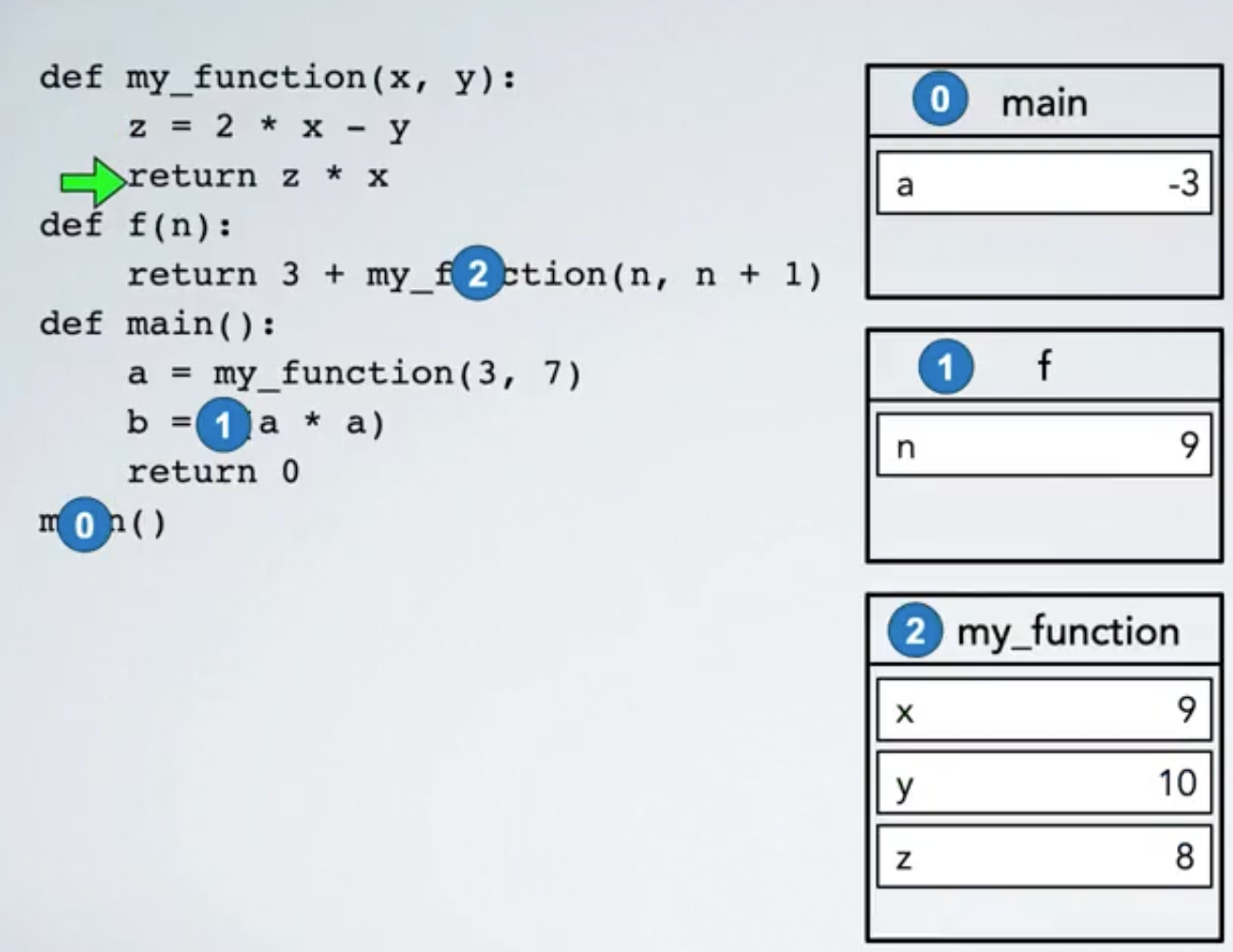

In this exercise, you will be provided a block of code and asked to diagram its execution on a whiteboard. The goal of this exercise is to get practice thinking through how Python executes functions and how values are passed among functions.

In particular, we would like you to write out function stack diagrams like those illustrated in the Coursera video on Functions:

The Code#

Below you will find the code we wish for you to execute and diagram. Please be sure to also read below the code for some additional notes on its content.

def f(x):

if x == 7:

warning = "f(7) is illegal"

print(warning)

return warning

return (x + 3) * 2

def g(x, y):

if not isinstance(x, int):

report = "x must be an int in g(x,y)"

return report

else:

try:

# Be aware:

# you can use `+` with two strings

# you can use `+` with two numbers

# you can't use `+` with an integer and a string.

# Doing so gives an error.

return x + f(y)

except:

return 42

def h(x, y):

return g(x, y - 3)

def main():

list_of_args = [(1, 2), ("hello", 4), (3, 10), (4, 3)]

# This for-loop loops over the list `list_of_args`.

# In the first pass, `args` will become the first entry in the list,

# which is the tuple (1, 2). Thus `args[0]` will be `1` and

# `args[1]` will be `2`.

# The second pass, `args` will become the tuple `("hello", 4)`.

for args in list_of_args:

i = args[0]

j = args[1]

print(f"i = {i}, j = {j}")

print(str(h(i, j)))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

New Things in This Code#

There are a couple things in this code that you have not encountered before. We promise they are not particularly difficult to understand, they’re just new.

isinstance()#

We haven’t gotten too far into the Python type system, but isinstance() is a function that checks whether the value associated with a variable is of a given type. It returns True if it is, and False if it is not.

# Is `x` an integer?

x = 5

print(isinstance(x, int))

True

x = "hello"

print(isinstance(x, int))

False

if without else#

In most examples we’ve seen, if has always appears alongside else. However, else is always optional with if. If if appears without an else, the indented code beneath if will run if the if statement is True, and it will be skipped if not. Then execution returns to normal.

So:

x = True

if x:

print("I only run if x is true")

print("I'm outside the if so always run")

I only run if x is true

I'm outside the if so always run

x = False

if x:

print("I only run if x is true")

print("I'm outside the `if` block so always run")

I'm outside the `if` block so always run

try-except Blocks#

The logic of a try-except block is that Python will try to execute the code in the try block, but if it is unable to execute the code without generating an error, it should run the code in the except block instead.

So if I wrote the function:

def add_numbers(x, y):

try:

total = x + y

return total

except:

print(f"Can't add {x} and {y}.")

Then tried to run it with one string and one integer as arguments:

add_numbers("banana", 3)

Python would try to execute total = x + y, but because that code would normally raise a TypeError because you can’t add an int and a string, Python would print out Can't add banana and 3 instead:

def add_numbers(x, y):

try:

total = x + y

return total

except:

print(f"Can't add {x} and {y}.")

add_numbers("banana", 3)

Can't add banana and 3.

if __name__ == "__main__":#

Why did we put the main() call under the if statement if __name__ == "__main__":? This if statement will be true anytime a .py file is directly executed (e.g., by clicking the triangle “play” button in VS Code). So it will behave exactly the way main() has operated in all the exercises you’ve done so far.

The if statement is commonly used in Python because it will not be true if someone imports this file into another program. When a file is imported into another program, Python runs most of the code in the imported file so the functions in the file will be available in the importing program. But since we sometimes have code we don’t want run in that situation, we put it inside an if __name__ == "__main__": statement.

From now on, you should follow the practice of putting the primary function call of your script in this if-statement.

What exactly is

__name__and why does it matter if it is equal to"__main__"? You don’t need to worry about understanding it, but if you’re curious: when a Python file is run, Python automatically creates a variable called__name__. If the file has been called directly, the value of__name__is set to"__main__". But if a file is imported (like when a file is run in the process of importing a module),__name__takes on the value of module name.